VP9 is the best unused codec today that can improve video quality and media experience in your WebRTC application. Lets see who is this codec good for.

Last year there were 3 video codecs available in browsers for WebRTC: VP8, H.264 and VP9. Now there seem to be 5, with the addition of HEVC and AV1. Let’s put some sense into what is really going on, and where does each of these fit, focusing on VP9.

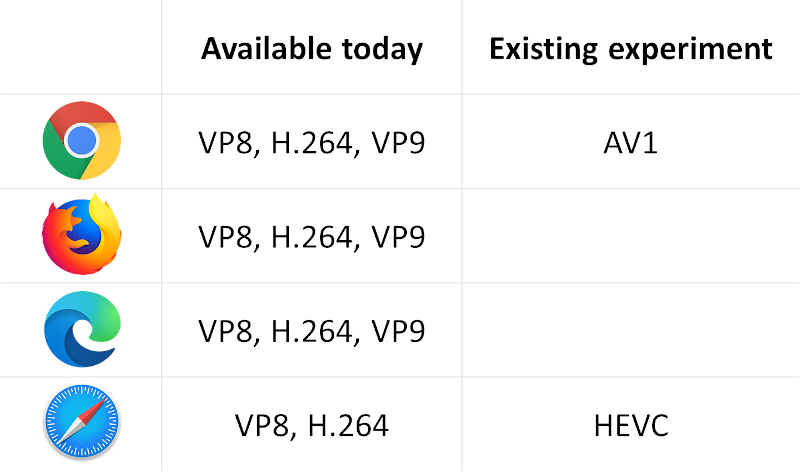

WebRTC video codec support by browser

In the good old days, WebRTC video codec support was “simple”. The industry was bickering and fighting between VP8 or H.264 until resolving the matter by mandating both VP8 and H.264 codec support in web browsers.

Then Google went ahead, adding VP9 into the mix. Mozilla went along with it and added it to Firefox.

After that, we’ve got to the point where the Alliance of Open Media was created with AV1 as its video codec, prepping us nicely into the next codec war we’re going to face – the upcoming AV1 codec versus HEVC – both of which are now available (or eminently available, or soon to be available) in web browsers with WebRTC.

I’ve created this simple table for you to understand in which web browser which video codec is available for WebRTC:

To make things simple, if you need to launch something in 2020, then the video codecs available to you are:

- H.264 and VP8 on ALL browsers

- VP9 on all browsers other than Safari

Which leads us to the next question…

HEVC & AV1. Should you join the experiment?

Let’s check the new video codecs that are sprouting in WebRTC to understand where we stand with them.

HEVC

It seems that Apple is adding HEVC to Safari. It is available to some extent in the Safari Technology Preview, so developers can tinker with it without knowing when it will be publicly available in Safari. And there is no indication or an inkling of an indication that other browser vendors are going to join – Google won’t. Mozilla definitely won’t. Microsoft just might, but that would mean forking away a bit from Chromium which is now the engine inside their Edge browser – not the right focus in my mind for Microsoft here.

HEVC is like VP9 in the same way that H.264 is like VP8:

- You need to deal with patent royalties when using HEVC (which are a litigation mess in the making)

- VP9 has less hardware acceleration available than HEVC

The only difference is that HEVC doesn’t exist in any browser yet and will only be available on Safari while H.264 is available in all browsers.

To understand where we’re at with H.264 vs VP8 we only need to read the stats shared by Google in their recent semi-celebration for 10 years of WebM and WebRTC:

“These technologies have succeeded together, as today over 90% of encoded WebRTC video in Chrome uses VP8 or VP9.”

The bolded marking is my own doing 😃 – and just so we’re clear:

- This is Chrome only

- It shows H.264 has less than 10% “market share” in Chrome WebRTC

- It also insinuates that VP9 doesn’t have a large “market share”, otherwise, a ballpark figure would have been provided. More on that later

- This is why I think HEVC doesn’t really stand a chance against VP9 in the context of WebRTC

Now with AV1 coming up and the huge backing behind it, the HEVC track is all but dead. At least for the majority of WebRTC developers.

👉 If you want to use HEVC in WebRTC, then you limit yourself to future Safari releases and native applications (where you modify the WebRTC codebase to add HEVC). Don’t expect it to work in any other web browser

AV1

AV1 is the best next thing in video coding. The best invention since sliced bread. The best unlikely cooperation amongst industry co-opetitors moving away from royalty bearing video codecs towards an open video codec.

It is supposed to be better than both VP9 and HEVC from a compression standpoint.

And it is supposed to be a coombaya experience where everyone is supporting it. The members list of the Alliance of Open Media foundation behind it is impressive. It includes all browser vendors and many chipset vendors. How can you go wrong here?

The only problem for me is adoption time. It takes a long time to get a video codec to market.

| Codec | Year started | Age |

| H.264 | 2003 | 17 |

| VP8 | 2008 | 12 |

| HEVC | 2013 | 7 |

| VP9 | 2013 | 7 |

| AV1 | 2019 | 1 |

To get a video codec to market properly time is needed. From specification, to implementation, to modifying the implementation to work for real time communications, to optimizing the implementation to work reasonably on available CPUs.

In Chrome it doesn’t officially exist. It is there behind a flag, making sure users can’t really enjoy it and web developers don’t have meaningful enough access to it.

Getting a codec that came out of the oven a year or two ago to production is risky business.

👉 If you need this article to learn about codecs, then AV1 should NOT be in your roadmap in 2020. You better wait this one out a little bit

Who is using VP9 codec today?

Google.

Not Google it. Google.

They use VP9 in Google Meet. That’s a large traffic source using VP9, but it says a lot about the adoption of VP9 so far.

There are also a few instances where VP9 is used in streaming or live streaming use cases. Nothing major though.

Adoption challenges of using VP9 codec

Why so low an adoption after being out on the market for 7 years?

I can only guess…

- It takes time. 7 years just isn’t enough when we’re still all figuring out WebRTC

- VP8 and H.264 is good enough for almost everyone

- VP9 requires more CPU than VP8 or H.264, and there are complaints about CPU use in WebRTC with these codecs already, so VP9 won’t help alleviate that problem – only worsen it

- Not enough hardware acceleration for VP9. There are more hardware decoders for VP9 today than they used to, but not much in the way of encoders. It does exist on Intel however, which is great

- Not enough knowledge and understanding on how to utilize VP9, so no one’s really trying it properly

- The popular open source media servers are all configured for VP8 or H.264 by default even if they do support VP9. And no one changes default settings. I would also assume and expect these open source platform to not optimize for VP9 anyways – not enough uptake yet

- The Alliance of Open Media and its success to put out such a strong cadre of supporters. By doing that, many large vendors in the industry are making the decision to “wait it out” with VP9 and skip this video codec generation directly to AV1

The benefits of VP9 codec

I’ve written about the role of VP9 in WebRTC before.

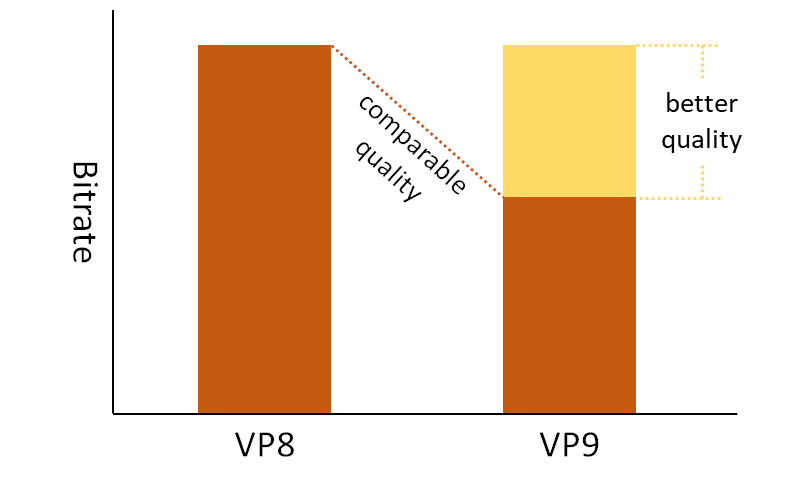

The premise of VP9 is improving encoding compression over VP8.

Compression rate

That comes at a cost of expending more CPU, giving us the option to balance between using network and CPU resources.

When looking at the higher end of the bitrate equation, one may prefer using VP8 or H.264 – we have enough network resources so we couldn’t really care on that front while saving on CPU might be beneficial

On the lower end of the bitrate equation, we’d want to squeeze every bit we have running on the network on higher quality. And then using VP9 might make more sense: since the bitrate is limited, we can spare more CPU on that and use VP9.

Sad thing is we can’t really know this in advance, at least not always.

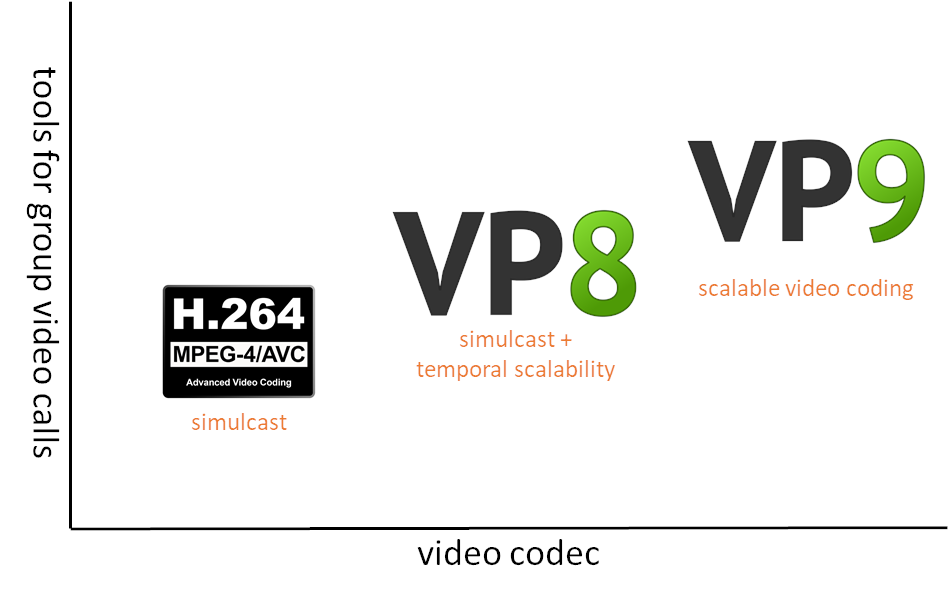

Scalability

Implementing a workable large scale video group call with WebRTC isn’t trivial. There are a lot of aspects to deal with both from a network perspective as well as from a CPU perspective.

The name of the game in this case is optimization, and this comes by having more flexibility in the tools you can use for optimizing the hell out of your video experience.

The flexibility here comes from VP9 SVC implementation in WebRTC:

- With H.264 and VP8 you can use simulcast – sending multiple video streams in multiple bitrates for the same content

- VP8 also supports Temporal Scalability – sending multiple frame rates in a single video stream

- With VP9 you can use SVC (Scalable Video Coding) – sending a single video stream with multiple layers for different resolutions, frame rates and quality levels

- To be clear, getting SVC to work in WebRTC isn’t easy, requires “reverse engineering” some of the workings of Google Meet and its proprietary SDP munging, but it might actually be worth the effort

If I had to chart the flexibility of a WebRTC video codec for large group sessions based on the tools it gives developers, this is what I’ll get:

👉 We expend more CPU on VP9 but we win in network performance and scalability of a video group call by doing that.

Plotting a route towards AV1

AV1 is the future.

Should you skip VP9 and just head to AV1 once it is ready? I don’t know.

The thing is, we had 2020. A pandemic that got us all cooped up at home doing video calls like crazy. The world has changed and with it priorities in our industry.

We’ve fast forwarded roadmaps by 5 years, so the future is already here. Can you wait a year or two more before you introduce a better video codec? If yes, then go straight to AV1. If you can’t, then you should seriously consider starting off with VP9 adoption.

A quick recap

Google Meet makes use of VP9 codec. Sadly, there is no other popular, large scale WebRTC application that makes use of it.

Yes. In fact, VP9 is the only codec today that supports SVC (Scalable Video Coding) in WebRTC. This gives developers more flexibility in large group video calls and even live broadcasts than other video codecs.

The challenge is that VP9 SVC support in WebRTC isn’t official or well documented.

Better compression rate compared to VP8 and H.264 which are mandatory to implement in WebRTC.

Better scalability. It has flexible tools that assist in scaling video group calls.

HEVC and AV1 don’t yet exist in WebRTC browser implementations. At least not in a way you can utilize in a production service.

VP9 is available and usable in Chrome, Firefox and Edge.

If you are looking to improve video quality or reduce bitrates in your WebRTC application, then you should seriously look at VP9.

One Note: Google Meet is rolling out VP9 on mobile, I think we are at 1% (this started last week). Until it is 100%, when a mobile joins, things fall back to VP8.

Phones that cannot encode VP9 will receive VP9 and send VP8.

wondering if you had a chance to look over the Amazon WebRTC offering called Chime

https://aws.amazon.com/chime/?chime-blog-posts.sort-by=item.additionalFields.createdDate&chime-blog-posts.sort-order=desc

Dan,

I don’t see Chime as an API platform, so haven’t included it. It is more like a UCaaS product that can be white labeled.

I also don’t understand what this has to do with VP9 adoption 🙂

Ohh, joy…

“H.266/VVC Standard Finalized”

Just what we needed an other codec 😉

This time supposedly with less patent problems.

Just saw that one myself. Wait 10 minutes until a press release is issued from AOMedia on AV2 just to keep us all confused.

While I do think AV2 is coming at some point, but judging by the timeline on your 2018 AV1-codec blog post I think it’s a bit early to expect something this fast, 2022 was on my mind.

I don’t think AV2 will be a thing in the next 5 years. I am also not sure how ready this VVC thing really is.

Does the iOS 14 VP9 implementation include hardware acceleration?

Is VP9 decoding more or less efficient than VP8?

I have no clue.

VP9 is not used because of its performance issues (I’m talking about libvpx now). It’s good on paper or in non-realtime / 2-pass encoding scenarios, but with -deadline realtime / –rt it’s actually A LOT worse than libvpx VP8, x264, x265, you name it

We tried VP8 and VP9 using Intel HW vaapivp9enc and vaapivp8enc in Gstreamer/Linux.

Finally we ended with VP8, because we could not make the vaapivp9enc to obey the output bitrate. It only worked in cqp configuration where HD/FullHD bitrate surged to over 11 Mb/s despite the limit of 3. VP8 behaved differently. Probably vaapivp9enc implementation has bug.

Unfortunately nobody among ATI/Nvidia does care about WEBvideo / VP9 encoding support despite the availability of a free HW encoder design for VP9. …

Thanks for sharing!

Hi Tsahi, thanks for the great post. Regarding the VP9 and HEVC they are both designed with HD and higher resolutions in mind, like 4K. With lower sizes they don’t offer much benefit. Also the libvpx is actually a very wild codec when it comes to the realtime encoding and its output bitrate ranges are all over the place without much of the bitrate and quality improvements over the H.264. So it is not only the matter of extra CPU usage, because all of those extra motion estimation and compensation an all other shiny tools need much more time or perhaps multiple passes to be effective. I am suspecting Chrome uses a specific implementation of the libvpx other than the opensource library, and this is just speculation. As for the AV1 currently it looks like the decoding complexity alone is on par with some encoding scenarios from H.264. For now the Dav1d looks to be providing one of the best decoder implementation and still it is very heavy. So I don’t believe the use of AV1 in webrtc or any other realtime usecase be a thing for a very long time, if ever. The most compelling candidate could be the MPEG 5 LCEVC, as an enhancement layer on top of either H.264 (or perhaps a better implementation of the VP9).

Behnam – thanks for these insights.

They are quite aligned with what I am hearing about VP9.